177: Radical Candor – How to Give Feedback with Kim Scott

/Giving feedback can be one of the toughest tasks for leaders. Many of us are reluctant to give feedback, partly from fear of seeming like a jerk. The best approach, according to bestselling author and former Google executive Kim Scott, is to care personally while challenging directly. She calls this radical candor. On this episode of The TalentGrow Show, Kim joins me to share how leaders can become great bosses without losing our humanity by leveraging the Radical Candor framework. You’ll learn how to give helpful feedback without falling into the common traps of obnoxious aggression, manipulative insincerity, or ruinous empathy, and why you probably need to reevaluate the way you think about praise and criticism. Plus, find out why it’s a mistake to avoid people who are mad at you! Listen to this episode and be sure to share it with others.

ABOUT KIM SCOTT:

Kim Scott is the author of the NYT & WSJ bestseller Radical Candor: Be a Kickass Boss without Losing your Humanity. Kim led AdSense, YouTube, and Doubleclick teams at Google and then joined Apple University to develop and teach “Managing at Apple.” Kim has been a CEO coach at Dropbox, Qualtrics, Twitter, and several other tech companies, and is the Co-Founder of Radical Candor, which helps companies build a culture Radical Candor.

WHAT YOU’LL LEARN:

What inspired Kim to write Radical Candor and how its success has impacted her (5:45)

Kim shares the story of one of the best moments of her whole career (9:53)

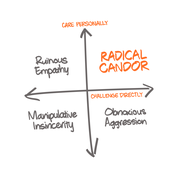

The Radical Candor Framework

Radical candor, obnoxious aggression, manipulative insincerity, and ruinous empathy: Kim explains each of these states and talks about where and how they tend to show up (12:30)

Why it’s important for managers to understand that when you tell someone something, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’ve heard, and how to get through to people better (15:36)

Kim addresses her use of the term ‘radical’ (20:21)

How do you care personally while challenging directly? (21:42)

The two best moments in your day to solicit feedback (23:15)

Why it’s a mistake to avoid people who are mad at you (25:51)

Reevaluating how we typically think about praise and criticism (26:33)

Kim shares what helped her get over her reluctance to give critical feedback (30:14)

Halelly and Kim discuss a controversial idea in a recent Harvard Business Review article (33:10)

What’s new and exciting on Kim’s horizon? (37:21)

One specific action you can take to upgrade your leadership effectiveness (41:24)

RESOURCES:

Check out Kim’s website

Connect with Kim on Twitter and LinkedIn

I’ve written about why you shouldn’t serve a feedback sandwich: how to give constructive feedback in a more palatable way, so check it out and stop it!

Episode 177 Kim Scott

SOUNDBITE: In my experience, by far the most common mistake is what happens when we do remember to show that we care personally. Most people are actually pretty kind people. But we’re afraid to challenge. We’re so concerned about not hurting someone’s feelings that we wind up in what I call ruinous empathy. We fail to challenge them directly. We don’t tell them something that they would be better off knowing, and we do them and the whole team and ourselves and our relationships a great disservice in ruinous empathy.

Because you’re withholding development from them.

Exactly. You’re withholding development from them. You may be wrong, actually. You may not be holding development from them. You may be wrong in your opinion, but by not sharing your opinion you don’t give them the opportunity to correct your opinion.

I love that.

INTRO Welcome to the TalentGrow Show, where you can get actionable results-oriented insight and advice on how to take your leadership, communication and people skills to the next level and become the kind of leader people want to follow. And now, your host and leadership development strategist, Halelly Azulay.

Welcome back TalentGrowers. I’m Halelly Azulay, your leadership development strategist here at TalentGrow and TalentGrow is the company that develops leaders that people actually want to follow. I founded TalentGrow in 2006 and I work with a variety of organizations to develop their leaders and help them get their leadership development strategy on point. This is the TalentGrow Show and this week we have Kim Scott, an author I’ve been wanting to get on the show for a while and I’m really excited to share with you about her best-selling smash hit, Radical Candor, and the philosophy or the framework that she shares about how to give feedback in a way that combines being caring and being direct. She also talks about some of the myths about how people think you should give feedback or how people are doing feedback wrong, and also about how some people are misinterpreting her words or the name of her book, really, without really reading her words, and doing it wrong. So, I also as you know, I try to help people stop doing feedback wrong and give more feedback in a meaningful and helpful way and I think this episode is going to help you out a lot. She of course shares an actionable tip as all of my guests do and we talk even about an article that came out in the Harvard Business Review recently that I read where they were putting down her work and the theme of her work and I allow Kim to address it directly. I hope that you enjoy this episode and let me know what you thought about it after. Without further ado, let’s listen to my conversation with Kim Scott.

Hey TalentGrowers, it’s Halelly here – just a quick note. I usually keep my show super squeaky clean because I don’t know if you’re listening while your kids are in the car with you or something like that – so I just wanted to give you a heads up that Kim uses the “S” word three times on this episode. I don’t think it’s a big deal and I left it in there, but in case you get little ones around, just wanted to give you a heads up here so that you don’t get surprised. Let’s do it!

Let’s do it I’m so excited to finally have Kim Scott on the podcast. I’ve been wanting to get her on for a long time. She’s the author of the New York Times and Wall Street Journal best-seller book Radical Candor: be a kick-ass boss without losing your humanity. Kim led AdSense, YouTube and Doubleclick teams at Google and then joined Apple University to develop and teach Managing at Apple. Kim has been a CEO coach at Dropbox, Qualtrics, Twitter and several other tech companies and is the co-founder of Radical Candor, which helps companies build a culture of radical candor. Kim, welcome to the TalentGrow Show.

Thank you. It’s an honor to be here.

Before you give us a brief overview about the main message in your book, I really would love for you to give us an overview of your professional journey. I always find that very interesting. Where did you start and how did you get to where you are today?

You know, it’s interesting. My very first job out of college was in Russia. I wound up starting a diamond-cutting factory, through a very strange set of circumstances. My job was to hire these diamond cutters, these Russian diamond cutters. The Soviet Union had just collapsed. This was in 1992 and I thought it was going to be easy because they were paid in Rubles which were worth nothing and I had dollars. I thought that was what management was, you pay people. No, that wasn’t what they wanted – they wanted a picnic. So we went into the outskirts of Moscow and we shared a bottle of vodka and by the time we had finished the bottle of vodka I realized that what they really wanted more than money was to know that if everything went to hell in Russia, I would help them and their families get out of the country. They wanted to know that someone would give a damn. That was the moment when management seemed interesting to me. Like, I can do that! I can give a damn. That was sort of the beginning of my management experience.

I left Russia and went to business school, and then I joined the Federal Communications Commission. I was one of the only people in my business school class to join the Federal government, which was an interesting ride, but very frustrating because it was so hard to get things done. I left there and joined the startups. That was another core management learning, mostly because the managers there were terrible. My boss was so abusive that I literally shrunk half an inch at that job. It was terrible! My doctor was like, “What is going on? You better quit this job.” I quit and I got my half an inch back which was good, I’m only five feet tall and I needed it! That got me to thinking, “What is it that makes a good boss and a bad boss?” I wound up starting my own company, thinking that if I were in charge, everything would be better and different. Of course it wasn’t. I made a lot of mistakes in my own company and some of which I’ll tell you about. Then that company wound up failing and I went to Google and I learned a lot of great management techniques. Then I went to Apple. I decided after six years at Google that what got me out of bed in the morning was not cost per click, it was the team. The team I was leading. Thinking about how to create environments in which everyone can do the best work of their lives. How to create these bullshit-free zones at work. But there wasn’t a job at Google where that was my day job.

Meanwhile my favorite professor from business school had left Harvard and joined Apple University and this was Steve Jobs’ effort to sort of throw away all management training and start from a blank piece of paper and say, “What should management really be?” So I of course had a great team to help design and teach a class called Managing at Apple. In the meantime, a friend of mine from Google had left Google and become the CEO of Twitter and he said, “Can you help me design a class called Managing at Twitter?” And as I was helping him, I realized managing at Twitter is pretty much the exact same thing as managing at Apple, as managing at Google, as managing at a bank, as managing in a warehouse. People are people. The cores of management are feedback, building a team, getting stuff done – pretty much are the same everywhere. That’s how Radical Candor was born. I decided to leave my job and write the book.

You left your job and wrote a book before you actually started your business?

Yes. Well, I thought, like all things in life I was wrong. I thought I would write Radical Candor in three months, because after all, I had designed this course at Apple and I knew what I wanted to say. It took me four years to write the book. It took a lot longer than I thought it would. But I love writing – I’ve actually written three novels before this – so I enjoyed it and so I just invested the time. I decided this was my gift to myself. I’m going to take this time, write the book I really want to write. Then I sold the book and then I started the business that really helps people roll out the ideas that are in the book.

You know, your book has had a very lasting and huge success I would say. Were you surprised by that and how have you found life with such a successful book?

It was the thrill of a lifetime. I mentioned, I wrote these other three books, one of which actually even got published. So I was not terribly optimistic about what would happen with Radical Candor. I really wrote it in part because I love writing, but also because I had become a CEO coach and that wasn’t failing. There were a lot of people who wanted me to be their coach and I only had enough time to be the coach for four or five people at a time. So I wanted to share the ideas that I had more broadly. So that was really why I wrote the book. I thought, if I don’t have time to coach people, at least I can send them this Google Doc and they can get the ideas that way. So I didn’t even know if it ever would get published. It’s been really, in a lot of ways, my business career was a way to subsidize my writing habit. I can finally make my earning as a writer, so it’s really thrilling.

I will say that probably the best moment in my whole career happened a few months ago when I was giving a talk about Radical Candor and a young woman came up to me afterward and she said, “You know, I became a boss for the first time, I became a manager for the first time about two months ago. I was having a really hard time.” She kind of teared up, it was clear that she had been having a seriously hard time. She said, “When I read your book, it was like having a friend or an older sister along with me to help me. And that is exactly, that’s why you write! You write because you want to reach out to your younger self. Anyway, it’s been really, really meaningful for me.

That’s wonderful. I can totally sense that. It’s very rewarding and as an author myself, it’s very rewarding when you connect even with one or two people that can articulate that meaningfulness to you about reading your book and then you say, “That’s why I did it.” It allows you to scale your impact and you really have scaled your impact. I have to tell you, I’ve been aware of your writing and your book and the ideas for a very long time, and in the back of my mind I’ve thought for a long time, “I should get her on the show.” But I didn’t have a direct connection to you and I often try to go to direct connections or indirect connections to invite people like you to my show. And then I was listening to one of my favorite podcasters, Amy Porterfield – I don’t know if you’ve heard of her name – because she’s talking you up on her show. Which is very cool because she’s an entrepreneur and she’s building as she called it a small and mighty team, but she’s not in the corporate world. And she was talking about how she didn’t really realize she was not necessarily a great manager to her growing team, and when she read your book she instituted it into her company. When I listened to that it was like, “Universe to Halelly! This is something you need to do. Let’s pursue.” And then the straw that broke the camel’s back is that I have a woman named Kristen White who transcribes my podcast for me so that people can read it when they cannot or don’t want to listen, and she wrote me and said, “We have a book club at work and we just read this book called Radical Candor by Kim Scott and I thought you should definitely have her on your show.” And I was like, “Okay, fine!”

Notes from the universe. Well, thank you universe. It’s great to be chatting now.

It’s very great. Enough of the teasing – let’s talk about Radical Candor. What’s the definition of radical candor and you have this cool two-by-two framework, can you describe that to us?

Absolutely. Radical candor really means caring personally at the same time that you challenge directly. And when you can both care and challenge at the same time, that’s radical candor. However, sometimes we forget to show that we care about people who we work with and we only challenge them and then we wind up in what I call obnoxious aggression, and very often when we wind up in obnoxious aggression, when we realize we’ve behaved like a jerk, instead of moving the right direction on the care personally dimension of radical candor, we move in the wrong direction on challenge directly and we wind up in the very worst place of all, manipulative insincerity. That’s what happens when you neither care nor challenge. That’s where backstabbing behavior, political behavior, the false apology, all the kinds of stuff that makes a workplace really pretty toxic creeps in. And it’s kind of fun to tell stories about obnoxious aggression and manipulative insincerity. We all have them. But in my experience, by far the most common mistake is what happens when we do remember to show that we care personally. Most people are actually pretty kind people but we’re afraid to challenge directly. We’re so concerned about not hurting someone’s feelings that we wind up in what I call ruinous empathy. We fail to challenge them directly. We don’t tell them something that they would be better off knowing, and we do them and the whole team and ourselves and our relationships a great disservice in ruinous empathy.

Because you’re withholding development from them.

Interviewee: Exactly. You’re withholding development from them. You may be wrong, actually. You may not be holding development from them. You may be wrong in your opinion, but by not sharing your opinion you don’t give them the opportunity to correct your opinion.

I love that.

So it’s in one of two ways problematic.

Great point. I’m so glad you made it.

The other thing that happens in ruinous empathy is often, we get more and more frustrated when we’re there. Somebody does something, it frustrates us, they do it again because they don’t know that it frustrates us. So we get more frustrated and eventually, you wind up exploding. By the time you finally say something, you wind up saying it in a way that’s really is not especially helpful or kind. That’s a very common hero’s journey to obnoxious aggression.

Yes, because you’ve moved away from being passive about it, but it’s no longer just a small tweak that you’re suggesting.

Exactly.

It’s been bottled up and I think this is where the HR people get a call. “I need to get rid of this person, how can I do it?” And they’re like, “Have you talked to them?” No. Well, okay!

Or, and I saw this over and over and over again, sometimes it felt like I was watching a slow-motion train wreck. You’ll tell somebody something and it’s hard to work up the courage to tell somebody something and then they don’t hear you. They don’t hear you at all. And yet you think you’ve done your job. You think you’ve told them. So very often, I would watch managers when I was at Google and I had a team of 700 people, so there were a lot of managers. A manager would come to me and say, “I have this problem on my team. This person is doing this thing,” and I’d say, “Have you told them about it?” “Yes, I’ve told them over and over again and it’s just not changing.” And then I’d bump into the person and ask them about it and they would look at me sort of quizzically, like, “What are you talking about?” It wasn’t that the manager was lying to me – they had told the person, but the person hadn’t heard. So I’ll give you an example. It is your job as the manager to be really clear, but it’s very hard.

I’ll give you an example about a time when my boss criticized me, shortly after I joined Google. I had to give a presentation to the founders and the CEO about how the AdSense business was doing. And I walked into the room and there was Sergey Brown, one of the founders, on an elliptical trainer in toe shoes, stepping away. And there in the other corner was Eric Schmidt, who was CEO at the time, and he was so deep in his email it was like his brain had been plugged into his computer. And like any normal person in this situation, I felt a little bit nervous – how in the world was I supposed to get their attention? Luckily for me the AdSense business was on fire and when I said how many new customers we had added over the last couple of months, Eric almost fell off his chair. “What did you say? What do you need from us to help – do you need more engineers? Do you need more marketing dollars?” I’m thinking the meeting is going okay. In fact, I now believe I’m a genius, and as I was walking out of the meeting I passed by my boss and I’m expecting a high five, a pat on the back, and instead she says to me, “Why don’t you walk back to my office with me.” And I thought, “Oh, wow, I have screwed something up and I’m sure I’m about to hear about it.” She started the conversation by telling me about the things that had gone well. Not in the sandwich sense of the word, but seeming to really mean what she was saying and telling me some things I didn’t know. But of course all I wanted to hear about was what I’d done wrong.

Eventually she said to me, “You said ‘um’ a lot in there, were you aware of it?” This point I breathe a huge sigh of relief, because if that was all I had done wrong, who really cared? I had the tiger by the tail and I said something like, “I know, it’s no big deal, it’s a verbal tick.” Then she said to me, “I know this great speech coach and I bet Google would pay for it. Would you like an introduction?” Once again, I made this brush-off gesture with my hand and I said, “No, I’m busy. Didn’t you hear about all those new customers? I don’t have time to go see a speech coach.” And then she stopped, looked me right in the eye and said, “I can see when you do that thing with your hands, I’m going to have to be a lot more direct with you. When you say ‘um’ every third word, it makes you sound stupid.” Now she’s got my full attention. Some people might say it was mean of her to say that I sounded stupid, but in fact, it was the kindest thing she could have possible done for me at that moment in my career, because if she hadn’t used just those words, she never would have gotten through to me and I never would have gone to see the speech coach. When I did, I learned that she was not exaggerating. I literally said ‘um’ every third word. I never would have learned that if she hadn’t said it to me in just that way, but she had to try three times to get through to me. That’s actually the rare person who when they finally get the courage to tell you this thing, when you don’t hear it, is willing to say it again. And then again. And to keep saying it more strongly until they get through to you.

That’s really what radical candor is. I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that she had my back, that she cared about me, which is part of what made it easier for me to hear what she was saying. But I also was grateful, maybe not in the moment, but a few days later, that she had the strength and the courage to challenge me so directly.

Why do you call it radical? It doesn't seem so radical.

It doesn’t seem so radical at all. Caring and challenging, doesn’t everybody do those things? But it’s rare. I call it radical because it’s very fundamental and very rare. One of the things I’ve heard since the book came out was maybe it was a mistake to call it radical. Maybe I should have called it Compassionate Candor. Because a lot of people hear the term radical candor and then they use it as an excuse to behave like a garden-variety jerk. That’s been one of the most painful bits of feedback I’ve gotten since the book has come out, because that obviously wasn’t my intention, but I’m afraid a lot of people do misuse the term in that way. In the second edition of the book I actually offer a different version of the framework in which the upper right-hand quadrant is called compassionate candor.

Interesting. But it’s the name of your company, right? It’s a little bit hard to swim back from it I guess any further than that. And it’s been successful.

It works. It’s very catchy. Like all catchy things, it’s prone to misinterpretation. The second edition of the book was really an effort to address that very important comment and very misunderstanding of the idea.

How do you show care personally while challenging directly? Do you have a quick framework for that?

Yeah, it is very easy for me to say be radically candid. It’s really hard for you to do it. So I have a lot of compassion for that. There are several things that I think can really help. One of the things that you can do that can help is to think carefully about the order of operations of radical candor. Don’t start by offering criticism. That’s another common mistake that people make about radical candor. The place to start is by soliciting criticism. When you solicit criticism, when you take a moment to really frame your question, your sort of “What could I do or stop doing to make it easier to work with me,” or however you want to say it. Another person I worked with, Christa Quarles who was the CEO of Open Table, said the question she likes to use is, “Tell me why I’m smoking crack?” Whatever your question is, ask it and ask it often. Make sure that people expect you to ask them for feedback about you and your performance.

And Kim let me stop you for just a second – I think I’m hearing that you are suggesting to do this in isolation, separately from the conversation where you have feedback to offer, is that true? Or is it sort of like step one, ask for feedback, step two, give feedback?

Separately. I think in general, there are two good moments in your day or in your week to solicit feedback from people. One of them is at the end of a one-on-one, so if you’re the boss, and by the way, one of the things that is hard about this advice is that I suggest that you do this for the people who work for you, but your boss may not be doing this for you. So sometimes this feels like a very lonely one way street, but it’s wroth it. It’s going to make your life better. I suggest if you have one-on-ones with the people who work for you that you let them set the agenda. That it’s their meeting and you’re there to address their agenda items, but save five minutes at the end and do this every time you have a one-on-one. Ask what you could do or stop, and ask it in your own words. Don’t use my words, but some way that you find natural and authentic and that really demonstrate that you want to hear what they’re going to tell you. But ask for some feedback. Don’t ask for feedback, ask for criticism. Let’s just keep blunt about it. What can I do differently? What did I screw up in that meeting? Tell me why I’m smoking crack. Whatever it is that you want to say to people, say it, ask it. And then you’re going to have to adjust it. Jason Rosoff who I started Radical Candor with, hates my question, what could I do or stop doing that would make it easier to work with me, because it feels to broad for him. For him, I need to ask, “In that meeting, what did I do wrong? Did I need to be more time bound or more specific, or I’m working on not interrupting people, how often did I interrupt people in that meeting?” It needs to be more specific for him. So you need to adjust it to yourself and then you need to tune it in again to the person you’re speaking to.

And I will say one thing – if everybody who is listening to this podcast does only one thing as a result of the podcast differently, it should be coming up with your questions, figuring out how you’re going to ask your soliciting feedback question, and ask it. Someone, today. Don’t wait until tomorrow, do it today. If you’re on your way home, ask a friend or your spouse or whatever. Solicit feedback first.

By the way, I said there were two times that are really useful for soliciting feedback. One is at the end of the one-on-one. The other time that’s really great to solicit feedback is when someone else is angry at you. As long as you, yourself, are not too angry. We tend to try to avoid people who are mad at us, and this is really a big mistake, because when someone is mad at you, they are more likely than in any other time to tell you the truth about what they really think. It may be kind of a harsh version of the truth, so make sure you’re prepared to hear it. But this was a tip that Alan Yousouf [sp?] who was a senior engineering leader at Google gave to me. He said, “Nobody ever told me the truth unless they were furious at me.”

That’s fascinating. I haven’t heard that before.

I thought it was good advice, so I pass it along.

So solicit first and solicit often. Next, you want to give more praise than criticism. One of the mistakes people make in thinking about praise and criticism, they think that praise is the way they earn the right to give the criticism, or praise is the way they show they care and criticism is how they challenge. But that’s incorrect. Both praise and criticism should both show caring and challenging. The reason why you want to offer more praise than criticism is because your job is really to paint a picture of what success looks like, and you’re going to have a much more beautiful picture with more positive notes in it. There’s a lot of research that shows you should give three times, five times, seven times as much praise as criticism. I think it’s dangerous to try to guide your relationships by a ratio, but just to sort of take a page out of Mike Robbins’ book and focus on the good stuff. That’s number two. First, solicit criticism, next give praise. Now you’re ready, and this is not like some kind of six-sigma long process. You can do all of this in the course of a day.

Now you’re ready to offer criticism. You want to make sure when you’re in the mindset of offering criticism that you’re thinking about it as a gift, not as some sort of kick in the shins, and that you’re offering it to help people grow. You want to be humble. The reason why I call it candor and not truth is because to me, candor says, “Here’s what I see. What do you see?” Whereas if you talk about truth, it’s more of a dominant stance, like, “I know the truth and you don’t.”

It assumes objectivity, whereas candor assumes subjectivity, it sounds like.

Exactly. You may be wrong. A very common reason, an excuse that people give for not giving feedback is, “I’m not sure I’m right.” It’s okay. Perfection and omniscience are not a job requirement for management. You will be wrong, all the time. And the faster you come to that, the better. So you want to make sure that you’re humble and that you state your intention to be helpful. Really good criticism is kind and clear. Good praise is specific and sincere. You want to make sure that you’re focusing on these things. Now, that’s all pretty abstract. The best criticism I’ve ever gotten in my life happened in these impromptu two-minute conversations. But telling people to start having these impromptu two-minute conversations is hard. Because we’ve been told since we learned to speak, if you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say it at all. All the sudden it’s your job to undo training that’s been pounded into your head since you learned to speak. So, I think one of the things that can be really helpful is to think about a moment in your life, or in your career, where you failed to give feedback. Just try to be nice, usually, and the consequences were really bad. If you can think of that story, it can be a real motivator for giving that impromptu criticism in the moment. You want to hear my story? Do we have time?

If it’s a quick story, it sounds great.

It’s a quick story. I had just hired this guy, we’ll call him Bob, and I liked Bob a lot. He was smart, he was funny, he was charming. He would do stuff like we were at a manager offsite once and it was a startup, very stressful time in the company’s history, and we were playing one of those endless get-to-know-you games. It was taking a lot of time and everyone was stressed, but nobody wanted to be the jerk to say, “I don’t want to play this game.” And Bob said, “Hey, I can tell everybody is kind of stressed out and wants to get back to work. I’ve got an idea and it’ll be really fast.” Whatever his idea was, it was fast, we were down with it. Bob said, “Let’s just go around the table and confess what candy our parents used when potty training us.” Really weird but really fast. Weirder yet, we all remembered. And then for the next 10 months, every time there was a tense moment in a meeting, Bob would whip out just the right piece of candy for the right person at the right moment. Bob was quirky but we loved Bob. He brought a little levity to the team. One problem was Bob. He was doing terrible work. He would hand stuff into me and there was shame in his eyes and I couldn’t understand what was going on. I learned much later the problem was that Bob was smoking pot in the bathroom three times a day, which maybe explained all that candy! But anyway, I didn’t know any of that at the time. All I knew was Bob is doing terrible work and I didn’t know what to say. So I would say something along the lines of, “Oh Bob, you’re so smart, so awesome, this is such a great start. Everybody loves working with you. Maybe you could just make it a little better.” Of course he never does and this goes on for 10 months and his teammates are increasingly frustrated by the fact that they have to redo his work, wait on his deliverables which are invariably late, and eventually the inevitable happens and I realize that if I don’t fire Bob, I am going to lose my best performers.

So I sit down with Bob, have the conversation that I should have started 10 months previously, and when I finished explaining to him where things stood, he kind of pushed the chair back from the table, he looked me right in the eye and he said, “Why didn’t you tell me?” And with that question going around in my head, with no good answer, he says to me, “Anyone tell me? I thought you all cared about me.” It was that moment, when really I’m tempted not to give someone some critical feedback, that always helps me get over the reluctance to do so. Because if you channel your desire to be truly kind, and you realize that telling the person this thing is the more kind thing to do in the long run, it becomes much, much easier for most people to do it.

I read the Harvard Business Review and one day I was reading one of my favorite authors, Marcus Buckingham, along with Ashley Goodall, had written an intriguingly titled piece called the feedback fallacy, where they seemed to be making the case about how feedback and most people when they think or say feedback they mean critical feedback and of course that’s just feedback, and they were kind of saying it’s harmful and you shouldn’t give it and they were mentioning there’s a popularity of things recently of things like radical candor – they kind of dropping names, hint, hint, and I wrote down this quote from the article: “Telling people of what we think of their performance doesn’t help them thrive and excel and telling people how we think they should improve actually hinders learning.” This baffled me so I thought, “I’ll ask right from you!” What did you think of that?

You know, it’s interesting. We had a conversation, Marcus and I, because it seemed to me that he was one of the people who interpreted radical candor as meaning obnoxious aggression.

I agree.

And he agreed by the end of the conversation. I think what he was really saying in that piece is that bad feedback is really harmful, and I agree with that. Obnoxious aggression is incredibly harmful, and doesn’t usually help people succeed. But, the fact of the matter is, if you are a leader, you are going to be making decisions about who gets promoted, who doesn’t get promoted, who gets a bonus, who doesn’t get a bonus, who gets this assignment versus that assignment. And you’re going to be making those decisions based on conclusions that you have drawn about people’s work and performance. If you don’t share your conclusions with people, then you don’t give them an opportunity to improve or to convince you that you’re wrong. So as long as the feedback comes with a big dose of humility, as long as it’s a conversation and not a monologue, and as long as it comes with a big dose of “I really care about you,” it’s invaluable part of management.

The other thing I think that he and I agreed on is that really good criticism and really good praise are the opposite sides of the same coin. You need to do both. Forehand and backhand of being a manager. You’ve got to be able to offer really useful praise, not the kind of praise that I gave to Bob in that story where I was like, “You’re so awesome,” really just a head shake. But really useful praise that shows you care about the person but also challenges them to do more of whatever it is that is good. You’ve got to give really helpful, clear, kind criticism that points out the things, the challenges directly, but also shows that you care about the person at a human level and that you have confidence in their abilities. I don’t know, I mean, if you’re not going to do those things, then you shouldn’t have management in my opinion.

Thank you. I agree with you, and I think that the two things you said at the beginning of how to give feedback, with radical candor, is two things that don’t happen in feedback conversation at all but are sort of laying the ground to give feedback, and that is to show vulnerability and openness to feedback yourself first, and that empowers them. Also, it shows that your intention is to have an open and two-sided kind of relationship. And the other one which you said – and I also teach this – to give more positive than negative and not to serve it in the sandwich, so that again, the interactions people have and their experience with you is not that you’re this evil monster that only comes out to bonk them on the head with something nasty.

Exactly. Very well said.

Thank you. Awesome. Well, Kim, I would love to talk to you for at least another three hours but we are running out of time, so I always ask my guests what is new and exciting on your horizon? What’s got you energized these days?

I’m writing a new book, and you can give me feedback on the title. The new book is called Just Work, get shit done fast and fair. It’s really about sort of gender injustice in the workplace. My goal is to break the problem down so that we can solve it. And so I’m breaking the problem down in two different ways. One is sort of categories of things that go wrong. My assertion is that the sort of atomic building blocks of gender injustice are bias, prejudice and bullying. And then when you add power on top of that, you get harassment, discrimination, abuse and violence. So, some lighthearted topics. But I think if we break them down. The other thing that I do is I talk very explicitly about things you can do, whether you’re the person harmed or the up stander, the observer of what happened, or the person who caused harm, how to go from being the bad guy to the ally, or the leader. Because solving this problem is going to take the effort of everyone involved and the problem of gender injustice is not only an injustice problem, it’s also a productivity problem. There’s a lot of important research that demonstrates this. This book, like Radical Candor, is taking me four times longer than I thought to write, but I’ve really been having a great time writing it and I hope that it’ll be really helpful for people.

It sounds very helpful, and it’s intriguing. It definitely is a good time for that kind of book because I think in the aftermath of the #metoo movement and all of the changes we’re seeing in our culture, I think people are primed and ready to think about solutions. I would just say that when I listen to the title, when you said it to me and I had no context whatsoever, I was intrigued but mystified, and after you explained it, I don’t think anything about that title gives any clues about the subject matter. It was so general.

Yeah, that’s the problem with the title. I agree. If anybody has any good answers, send me a note! Radical Candor I was calling Tough Love until Dan Pink set me straight, so I’m sure there’s something better than Just Work.

Okay. Well, I would love to hear more about it when it comes out and maybe we’ll have you back talking about that. What do you think?

That would be really fun. The other thing, by the way, that I’m working on that I’m really excited about is we’re creating a Radical Candor sitcom with Second City, the improv group in Chicago. It’s going to be really cool. It’s a great way for people to really rock the ideas at a more visceral level. A lot of people love reading the book, but they want some entertainment in addition, so this is our effort to create some management education that is also a lot of fun.

This will be that people can watch it on TV like Netflix or they have to go to a show?

They don’t have to go to a show. It is right now, we’re selling it to companies. But we’re going to try to figure out how to make it broadly available to people as well.

That’s brilliant.

It’s lots of fun.

I love it. That’s good.

It’s not your grandfather’s management training.

And 80s hair may be optional just for comedic effect, like those videos they make you watch. That’s awesome! I always ask my guests to give one specific action, but you actually already did, so I don’t know – I would definitely count that. You said that people should think about what their question is.

Yes, come up with your question. How are you going to solicit feedback from people, and who are you going to solicit it from and when are you going to do it? And do it. Actually do it. Don’t just write down the question, ask the question and see how it goes. You’re going to learn something useful.

Good. TalentGrowers, challenge on. Kim, it’s been so fabulous talking with you. I’m so glad we finally had the chance and I know people are going to want to hear more about you and learn more from you, so what’s the best way to do that? Online, on social?

So there’s RadicalCandor.com, the website, and there is @candor on Twitter and @KimBallScott is my personal Twitter handle.

We’ll link to all of that in the show notes and Kim, thank you so much for your time and for sharing your insights on the TalentGrow Show.

Thank you so much. Really enjoyed the conversation.

It’s a wrap TalentGrowers, that was so fascinating to me. I really enjoyed talking to Kim. I’m so glad that she came on, and I hope that you enjoyed it as well and that you learned from it. I want to hear – what did you learn? What are you trying? What have you tried? What’s worked? How does it work? What’s changed? Let me know. I’m eager to hear from you. I also hope that you are taking advantage of the free tools that I have, for free, for download on the website, just for you listeners of the TalentGrow Show. It’s called “The 10 mistakes that leaders make and how to avoid them.” And we don’t want to be making mistakes, so get that tool and that will allow you also to hear from me every Tuesday and let you know what is the new episode, what’s coming up next week? I only tell my newsletter folks which episode is coming up next week, and you can be one of those people that hears about that, as well as tips and learning opportunities. Get on that list TalentGrowers. I look forward to being in touch with you. Thank you so much for sticking around to the end of the podcast club, and I look forward to talking with you again next week here on the TalentGrow Show. I’m Halelly Azulay, your leadership development strategist at TalentGrow, and until the next time, make today great.

Thanks for listening to the TalentGrow Show, where we help you develop your talent to become the kind of leader that people want to follow. For more information, visit TalentGrow.com.

Get my free guide, "10 Mistakes Leaders Make and How to Avoid Them" and receive my weekly newsletter full of actionable tips, links and ideas for taking your leadership and communication skills to the next level!

Don't forget to LEAVE A RATING/REVIEW ON APPLE PODCASTS/iTUNES! It’s easy to do (here’s how to do it in 4 easy steps). Thank you!!

Like the Facebook page of The TalentGrow Show!

Join the Facebook group – The TalentGrowers Community!

Intro/outro music: "Why-Y" by Esta

You Might Also Like These Posts:

Ep057: How to be better at receiving feedback with Sheila Heen

Ep036: Fierce Leadership, Radical Transparency, and Deeper Human Connectivity with Susan Scott

The "STS Formula" for giving positive feedback and appreciation